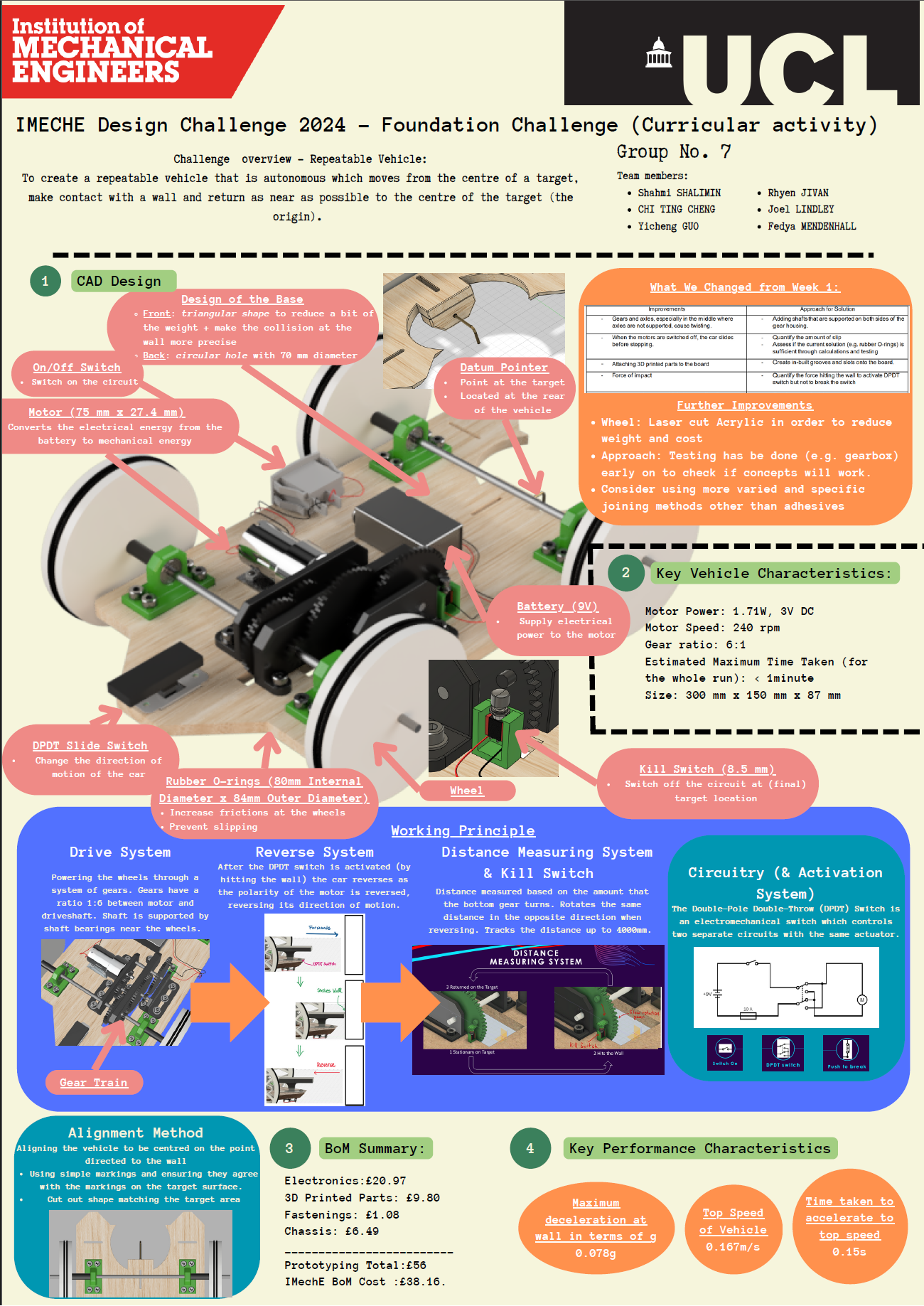

IMechE Repeatable Vehicle Design Challenge

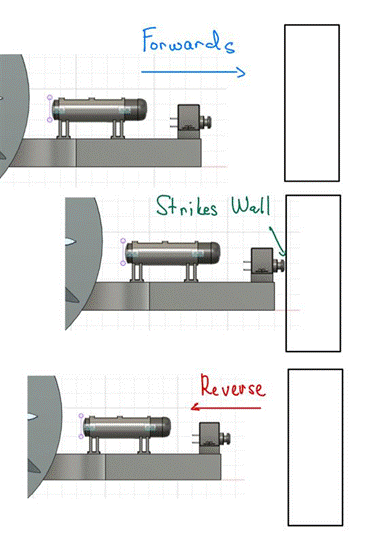

A two-week engineering challenge to design an autonomous mechanical vehicle capable of travelling forward, hitting a wall, and returning to its start point — with no programming or electronics.

Project Overview

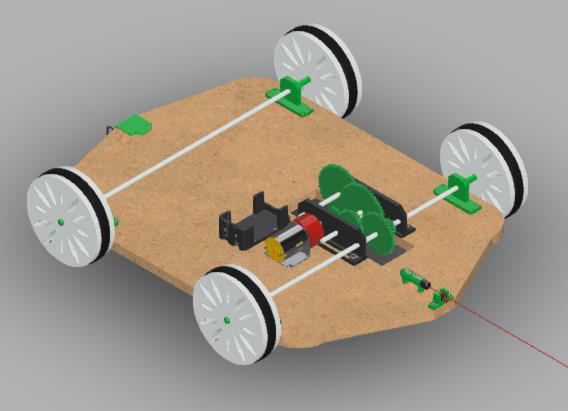

The IMechE Design Challenge tasked us with designing a fully autonomous repeatable vehicle capable of travelling from a defined start point, colliding gently with a wall, and returning precisely to the origin—without any programming, electronics, or remote control.

Working across UCL’s Scenarios Week, we approached this as professional engineers: understanding requirements, analysing constraints, generating concepts, modelling mechanisms, and producing a fully justified virtual prototype ready for manufacture. This project combined teamwork, engineering analysis, CAD modelling, and rapid decision-making under pressure.

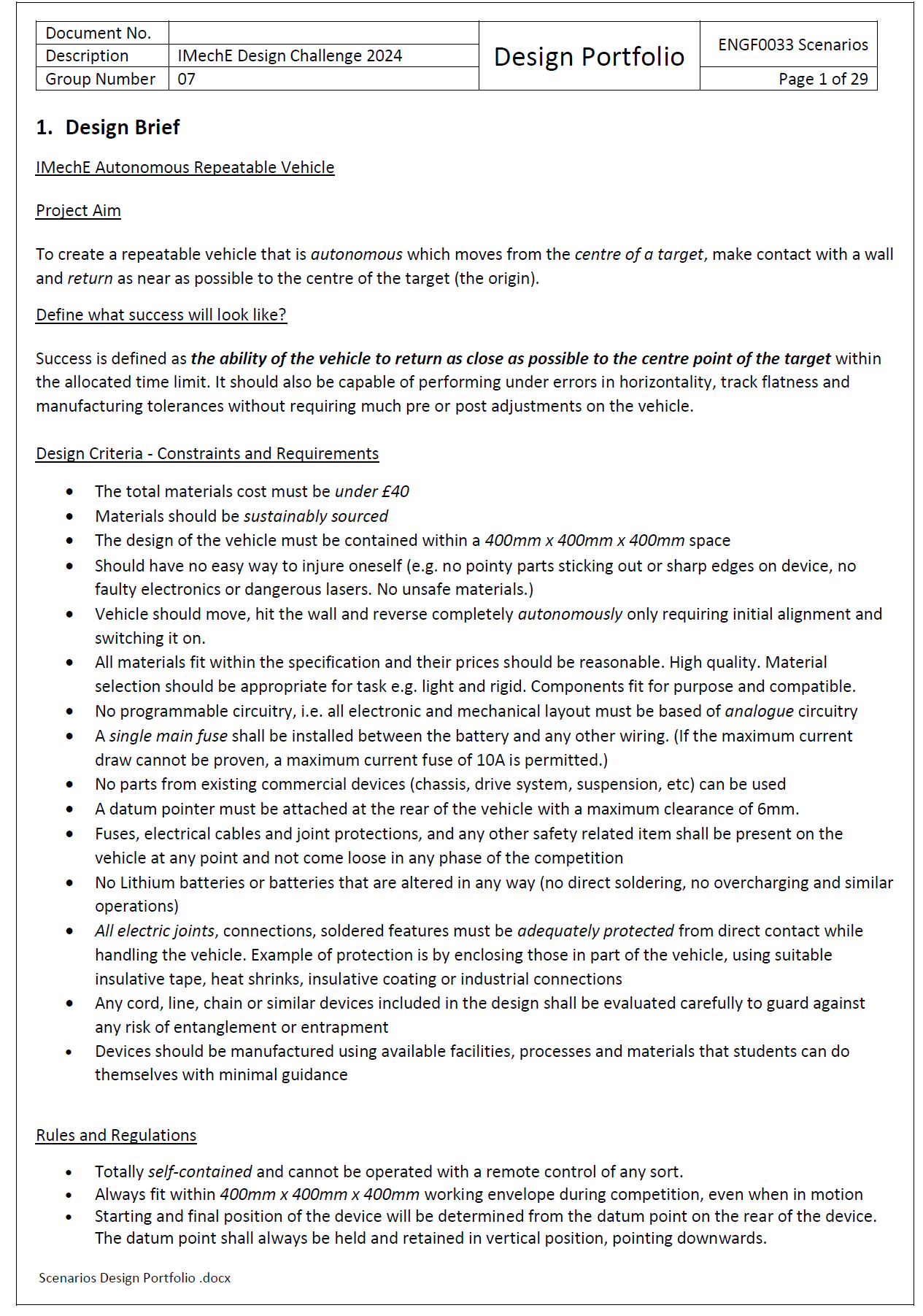

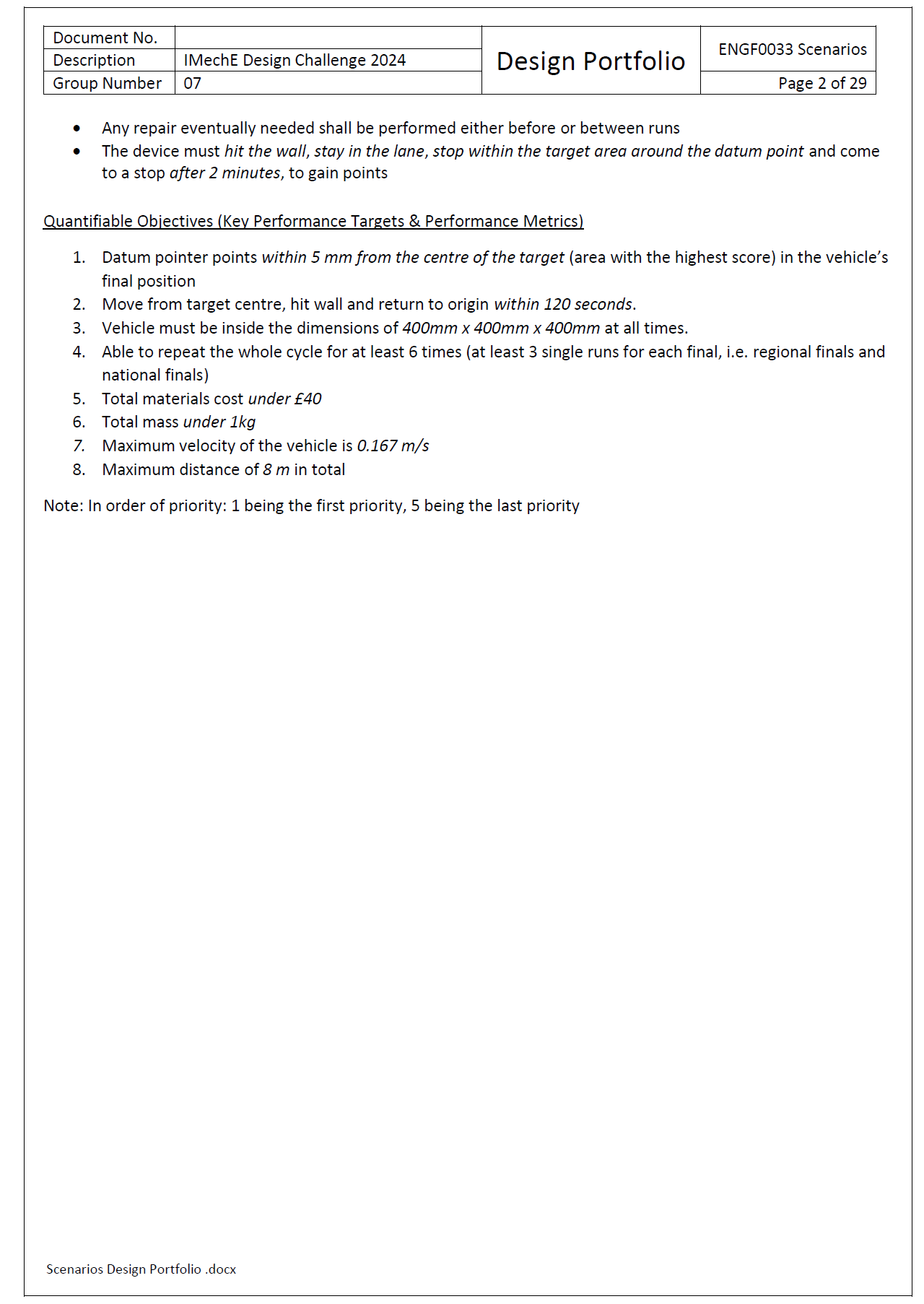

Challenge Requirements

Our vehicle needed to meet the following strict criteria:

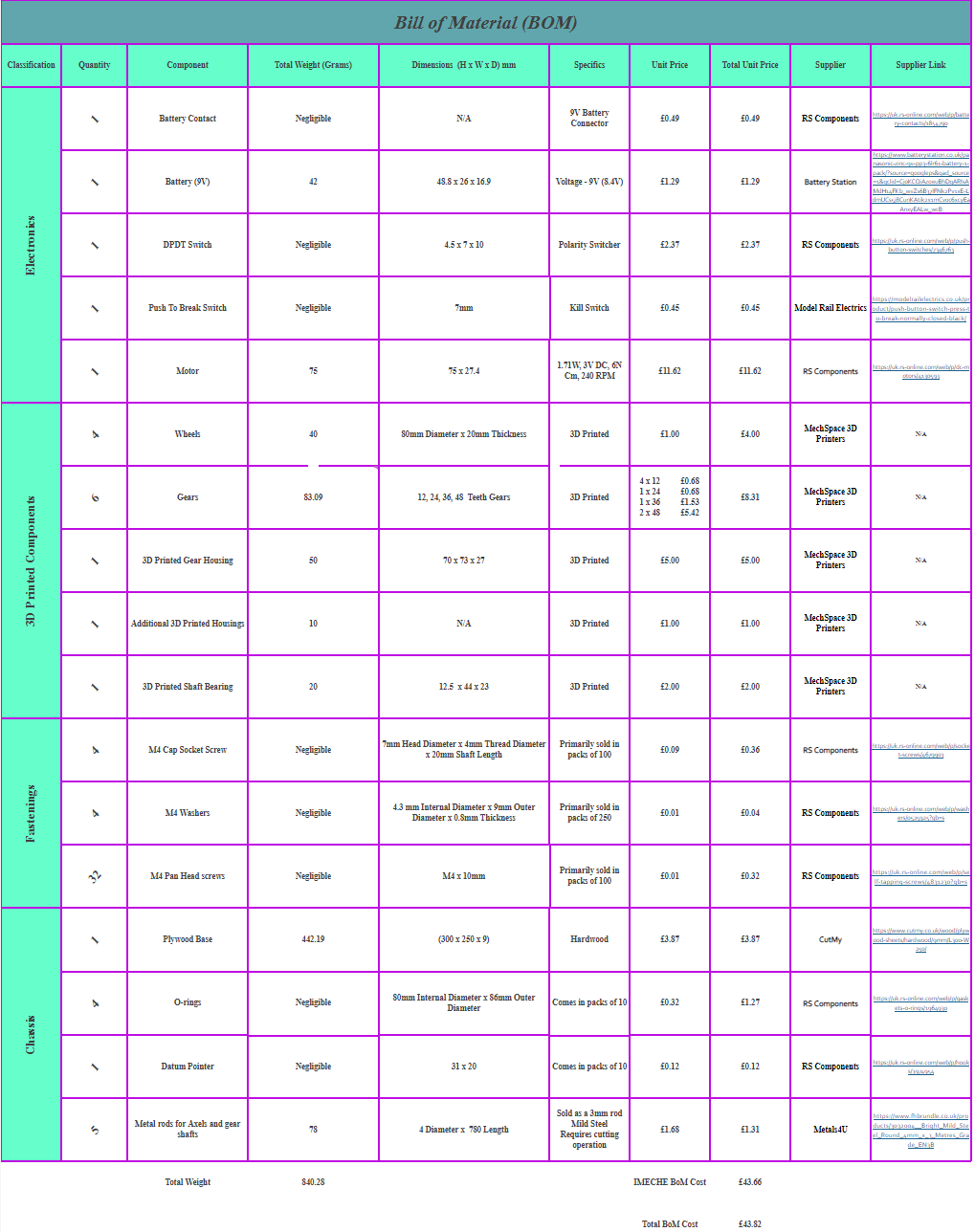

£40 total material budget

Must fit within 400 × 400 × 400 mm

Entirely mechanical — no electronics or programming

Travel forward → touch a wall → return to start

Datum pointer must finish within 5 mm of the origin

Must complete operation within 120 seconds

Safe, stable, and fully self-contained

Demonstrate repeatability, not just single performance

These constraints shaped every design decision we made.

My Role - Team Lead & Mechanical Designer

As Team Lead and Mechanical Designer, I was responsible for:

Leading the design direction and team coordination

Creating the complete CAD assembly in Fusion 360

Performing gear ratio calculations and mechanical modelling

Designing the drive system, reverse mechanism, and impact system

Producing analytical graphs and simulations

Preparing deliverables and presenting our engineering justification

Creating a Bill of Materials and managing costs.

This role combined leadership, mechanical reasoning, and technical execution.

Phase 1 - Problem Exploration

Interpreting the Brief

Our first task was to translate the specification into a set of engineering challenges. The core difficulty was achieving consistent, repeatable motion using only mechanical components. Factors such as surface friction, wheel slip, alignment, motor variability, and impact behaviour all significantly influence accuracy.

Key Engineering Challenges Identified

Ensuring consistent forward motion without wheel slip

Creating a reliable, fully mechanical reverse trigger

Mechanically measuring distance without electronics

Designing a safe and predictable wall collision system

Controlling the return behaviour to end within 5 mm

Keeping costs and manufacturing complexity low

Understanding these challenges guided our research and concept generation.

Phase 2 — Research & Concept Development

Early Concepts and Exploration

We explored several mechanisms across five subsystems:

Drive System: motor-driven gear train, 4-wheel drive

Distance Measurement: slow-tracking gear, belt-based measurement, mechanical counters

Reverse Mechanism: DPDT mechanical switch, spring reset, wall-trigger levers

Alignment: laser pointer with ground marking guides

Impact System: rigid stops vs. spring dampers

Each concept was evaluated against repeatability, safety, manufacturability, and compliance.

Concept Selection

Using a weighted decision matrix, we selected the following configuration:

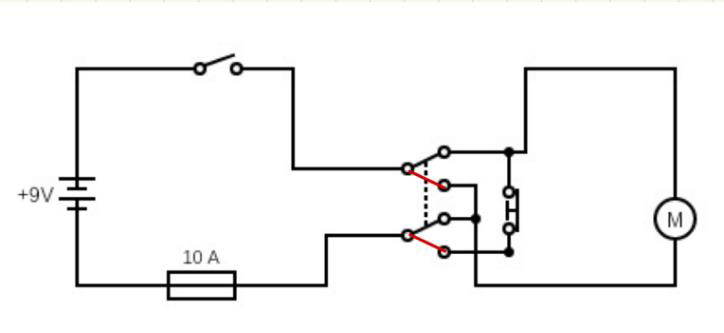

A DPDT toggle switch to reverse motor polarity upon wall contact

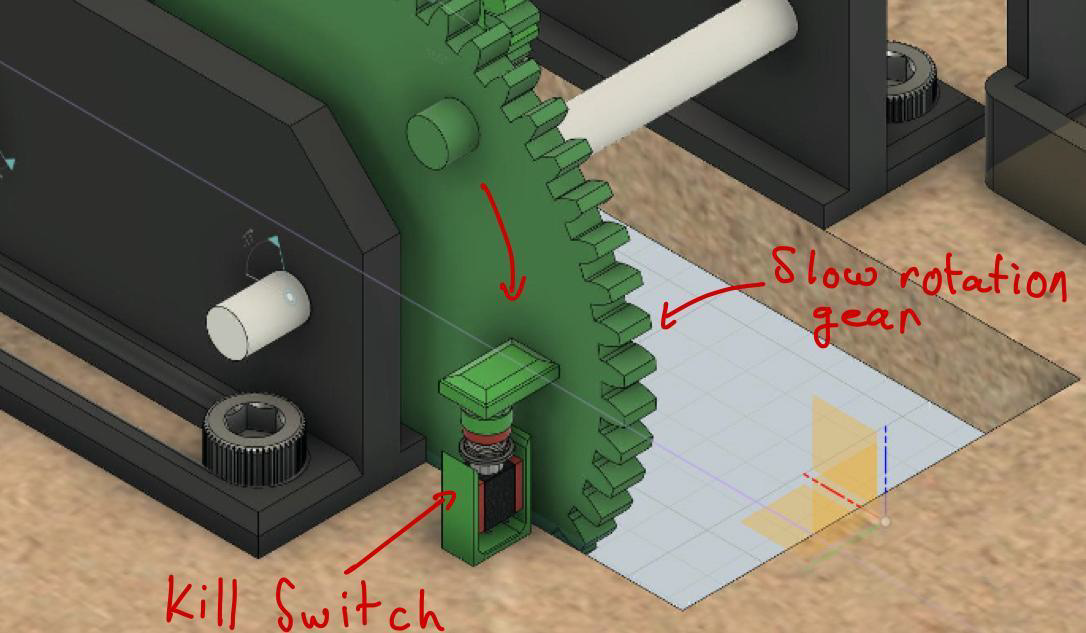

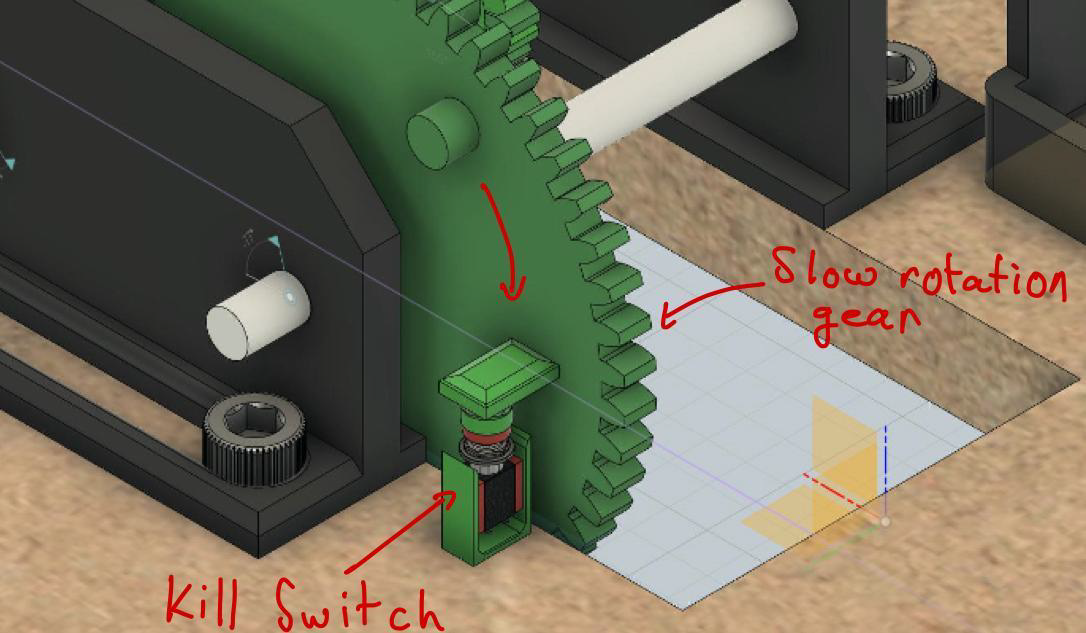

A slow gear (1:16 ratio) for accurate travel measurement

Laser alignment system to improve start-line precision

A front-mounted spring damper to absorb collision forces

A high-traction wheel system to minimise slip

This combination offered the best balance of simplicity, accuracy, and reliability.

Phase 3 — Engineering Modelling & Analysis

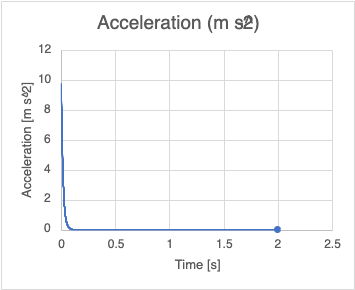

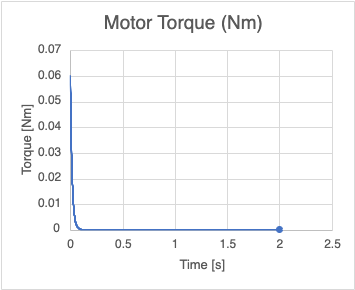

Kinematic and Dynamic Modelling

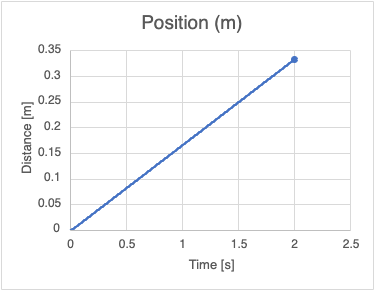

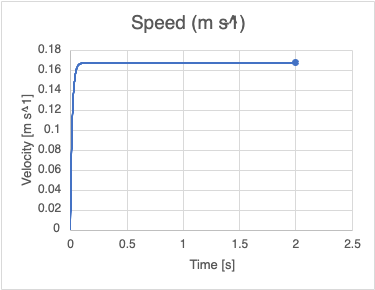

Using mathematical modelling, we evaluated the vehicle’s motion across the full travel path.

Key results from our modelling:

Top speed: 0.167 m/s

Time to reach max speed: 0.15 seconds

Impact deceleration: 0.078 g

Impact force: 0.71 N

Estimated round-trip time: < 60 seconds

Friction requirement: μ ≥ 0.6 for reliable traction

We modelled position, velocity, acceleration, torque, and power to verify the motor and gear ratios were suitable.

Wheel Slip Analysis

Surface friction was identified as a major source of error. To mitigate slip:

O-rings were added to increase wheel traction

The vehicle mass distribution was adjusted to increase normal force

Wheel diameter and material were selected to minimise variability

Collision Behaviour

We validated that a spring constant of approximately 2100 N/m would safely control deceleration without causing rebound or excessive stress on the reverse switch.

These analyses ensured the design was justified using engineering principles.

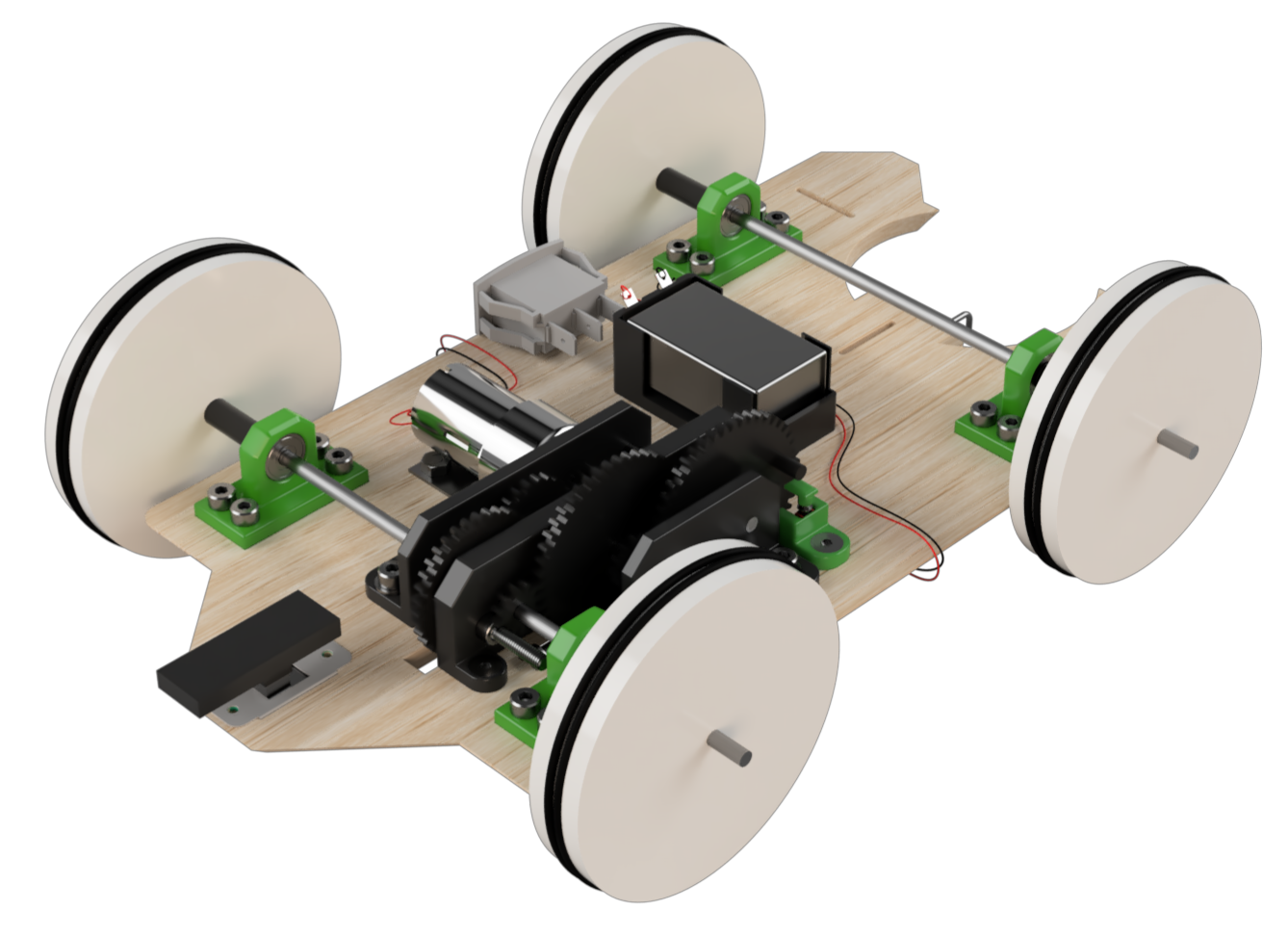

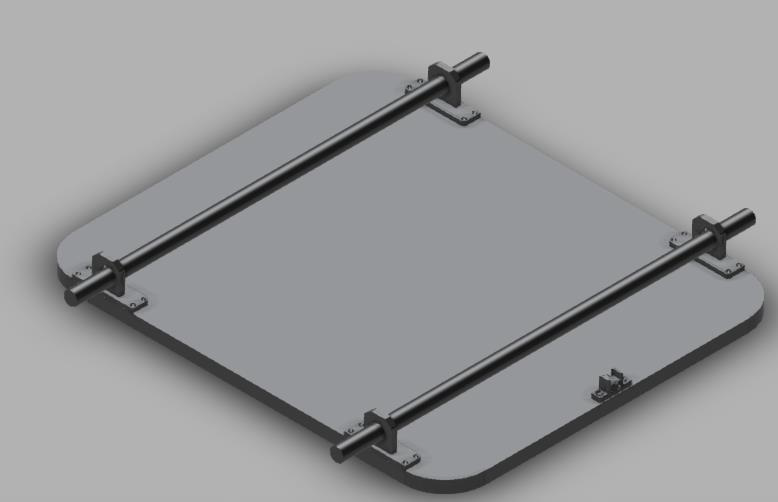

Phase 4 — CAD Development

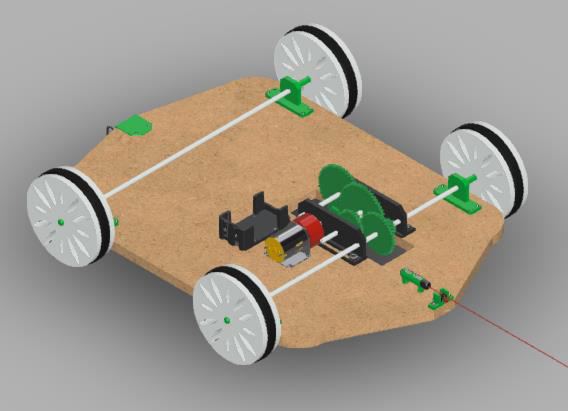

Modelling the Vehicle

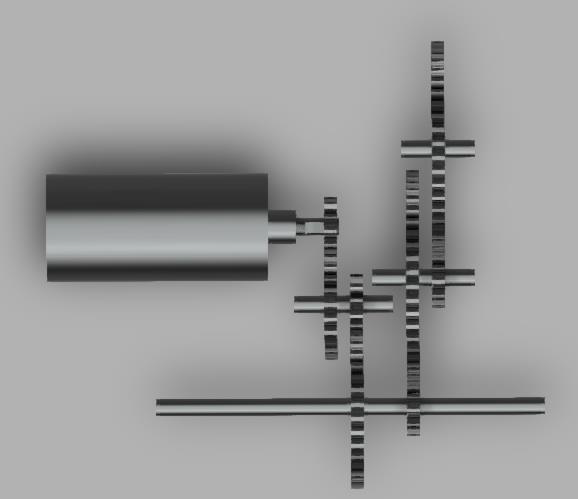

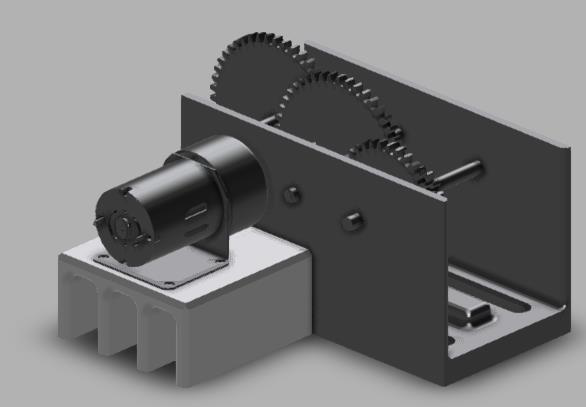

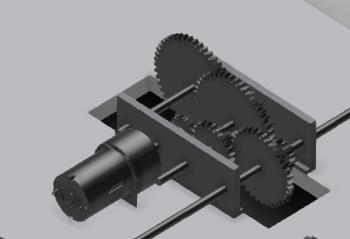

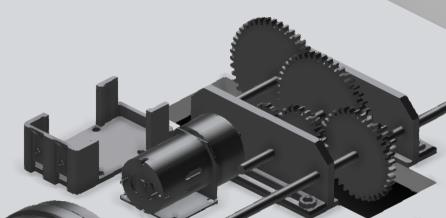

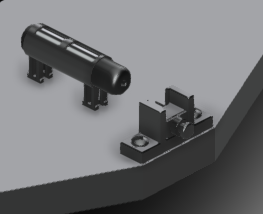

I developed the complete CAD assembly, starting with individual subsystems before integrating them into a coherent final design. The CAD model included:

Frame and housing

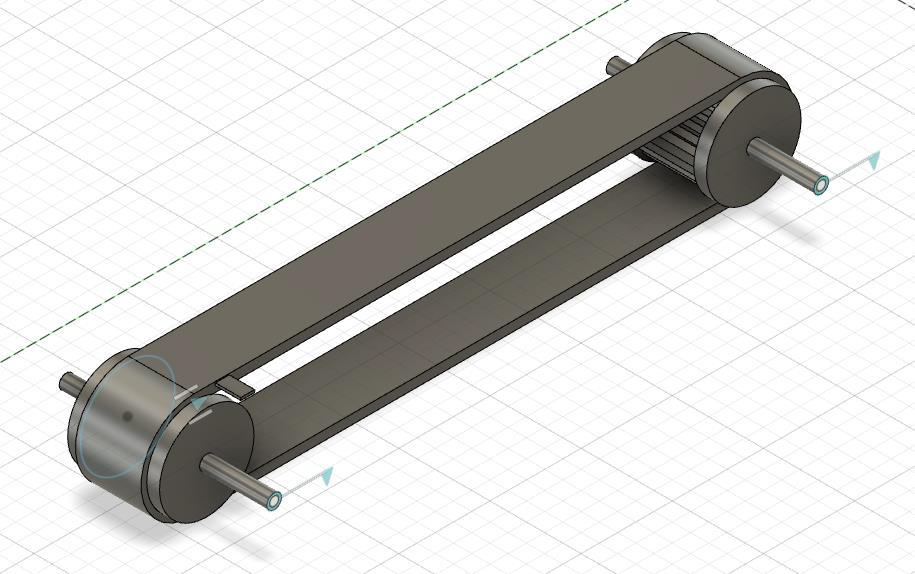

Gear trains for both drive and distance systems

Motor mount

Reverse-trigger housing

Datum pointer

Spring-damper for impact

O-ring wheels

Laser support bracket

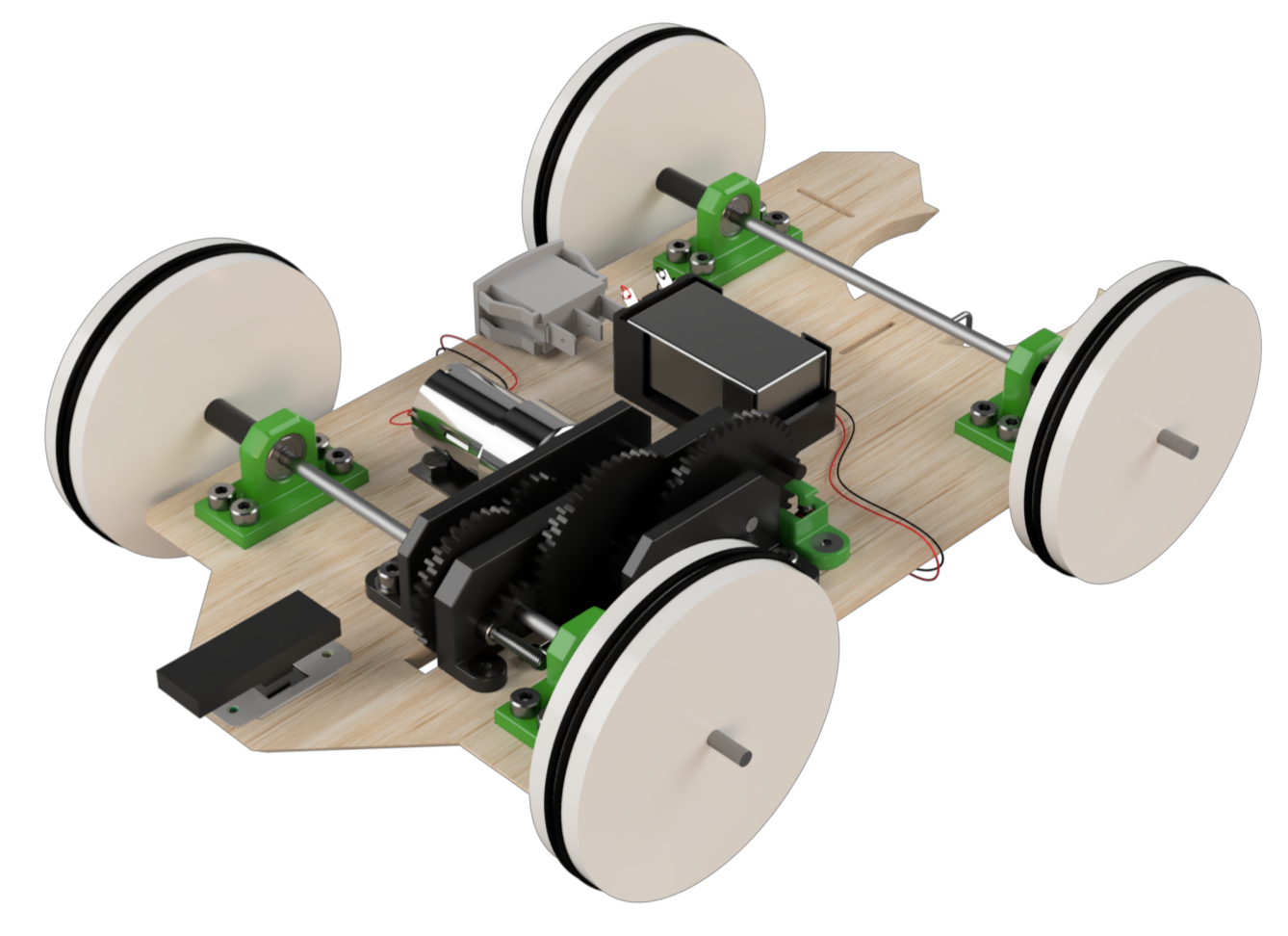

Iterative Refinement

Across iterations, improvements included:

Weight reduction through material removal

Improved motor alignment

More robust mounting for the DPDT switch

Redesigned front housing for consistent wall triggering

Greater clearance for gears and shafts

These refinements made the design more robust and manufacturable.

Phase 5 — Week 1 → Week 2 Improvements

Between weeks, we implemented significant optimisations:

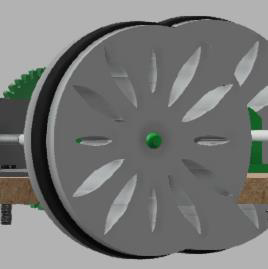

Replaced heavy wheels with lightweight acrylic wheels

Added earlier subsystem-level testing

Reinforced joints and mounting points

Improved gear housing to reduce backlash

Optimised reverse switch contact geometry

Refined alignment system for more repeatable starts

These changes greatly improved expected reliability and repeatability.

Subsystem Details

Drive System

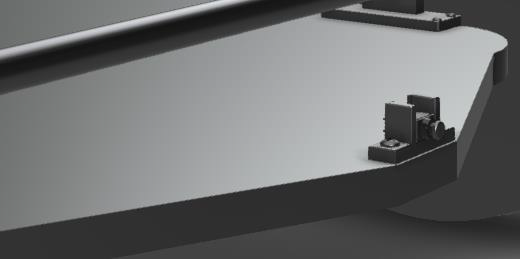

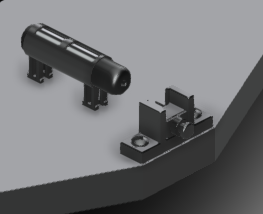

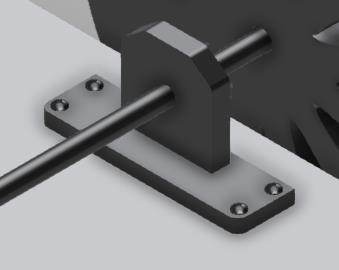

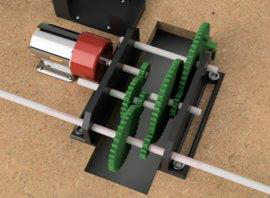

Reverse DPDT Mechanism

Distance Measuring System

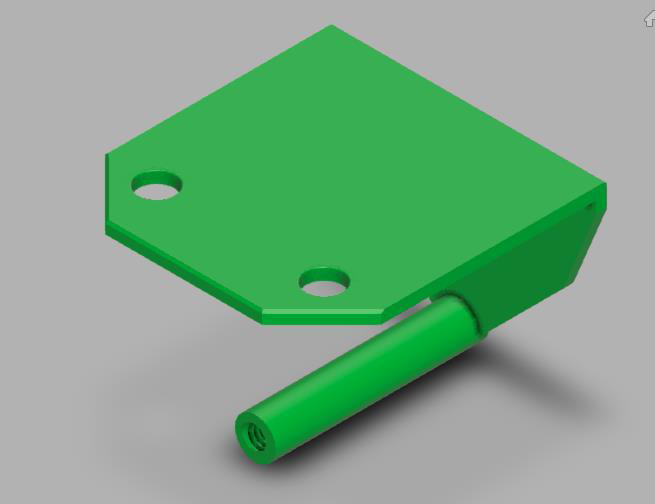

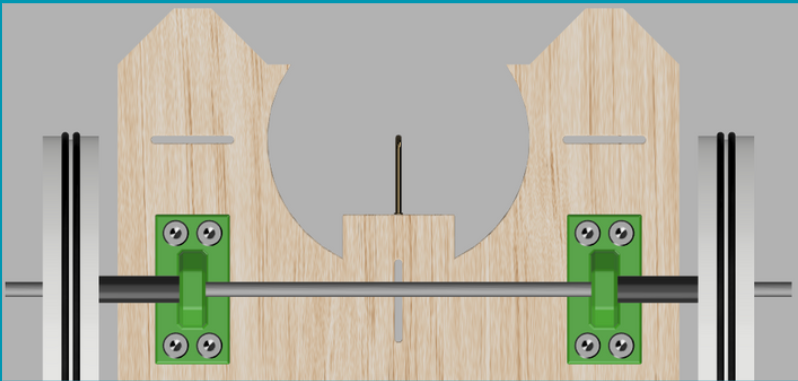

Alignment System

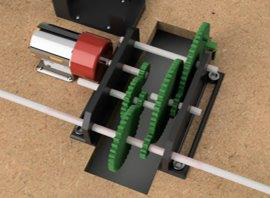

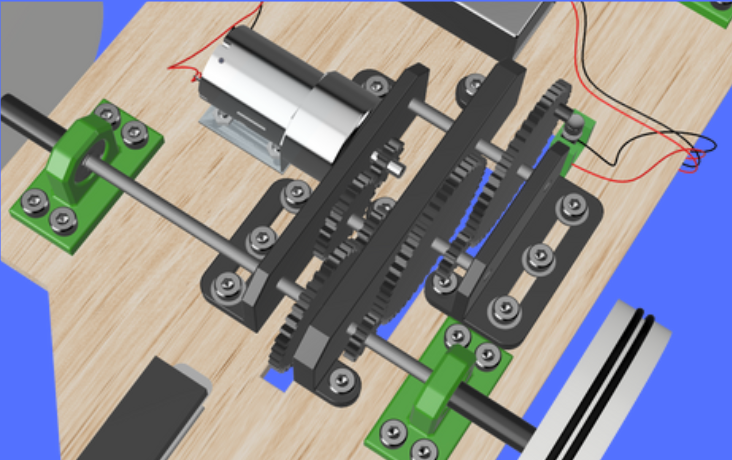

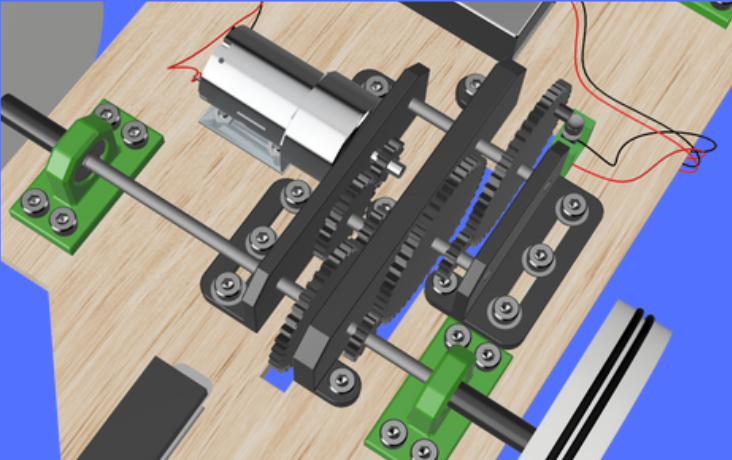

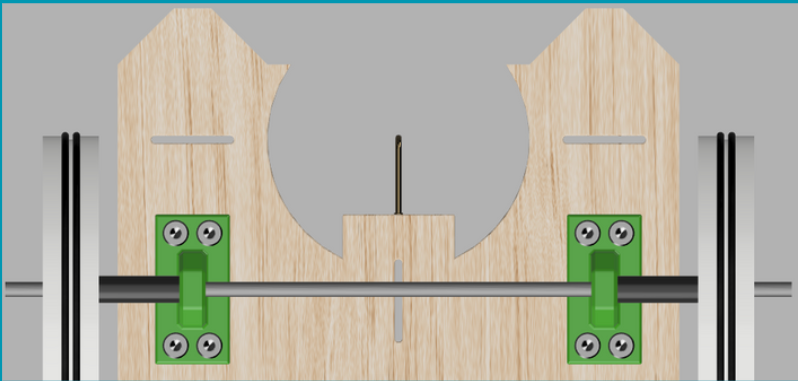

The initial gear housing was too cramped to accommodate the mechanism reliably, so it was redesigned into two sections: the first driving the front axle and the second containing the kill-switch assembly. The image also shows the O-rings added around the acrylic wheels to increase traction and reduce slip.

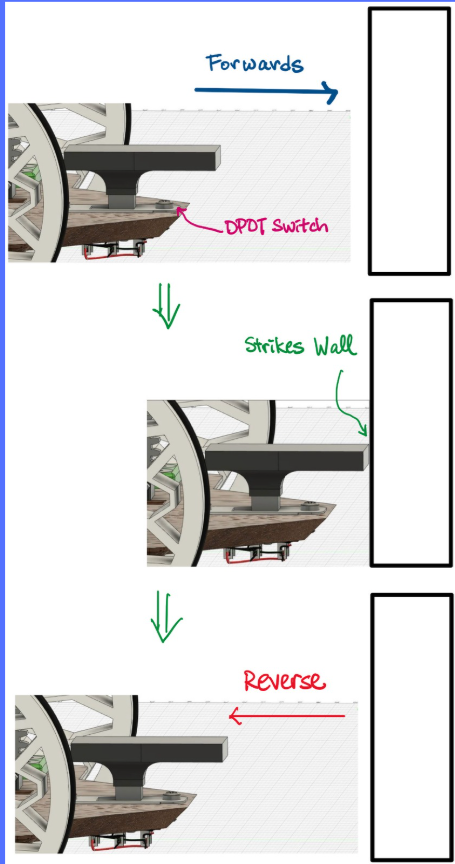

When the vehicle reaches the wall, the custom-designed cap presses against it and triggers the DPDT switch. This action reverses the motor polarity and initiates the return motion.

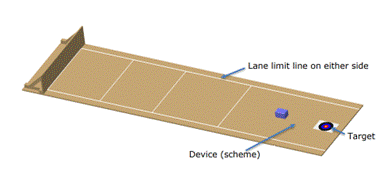

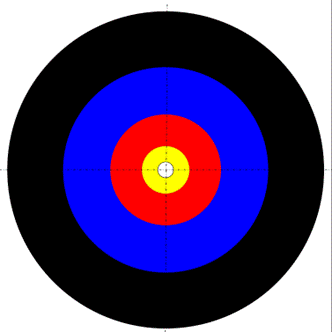

Starting target

By isolating this switch from the main circuit during forward motion, the cylindrical protrusion can activate it only on the vehicle’s return, cutting power precisely when it reaches the starting position.

The laser pointer system proved insufficient for reliably aligning the vehicle with the target. Instead, the diameter of the red target was cut into the rear of the vehicle’s base, along with three slots that match the dotted guide lines. The datum pointer also aligns with the white circle at the centre, ensuring precise and repeatable positioning.

Expected peformance

Our final predicted performance metrics:

Return accuracy: ±3 mm

Total cycle time: < 60 seconds

High repeatability across multiple runs

Stable collision response without rebound

Effective power transmission using 1:6 and 1:16 gear ratios

Fully mechanical autonomy with no electronics

The system met all IMechE requirements with strong safety and reliability.

Final Outcome

The final design is a fully justified mechanical vehicle ready for manufacture and testing. The CAD model accurately represents a buildable prototype, supported by modelling, analysis, and subsystem integration. Each element—from the gear train to the reverse mechanism—was engineered for reliability, simplicity, and repeatability under real conditions.

The project demonstrates strong mechanical engineering principles, teamwork, and effective technical decision-making within tight constraints.

Reflection

This challenge developed my skills in:

Mechanical system design

CAD modelling and design iteration

Gear ratio selection and kinematic analysis

Engineering justification and documentation

Team coordination and time management

It also reinforced the importance of subsystem testing, friction management, and early validation. With more time, I would refine materials, optimise assembly tolerances, and explore additional alignment methods to reduce systematic error even further.